Defining Generative Art and Its Essence

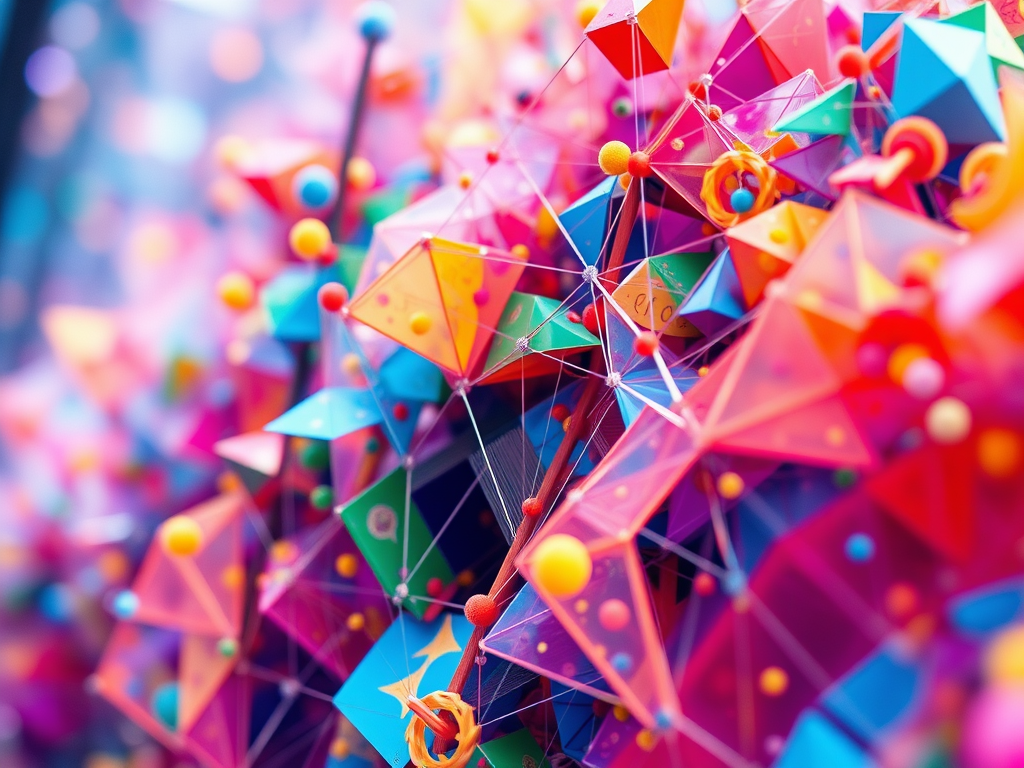

Generative art is a distinct form of creative expression that involves creating artwork through the use of autonomous systems. As Neeraj Pandey defines it, generative art is “art created through the use of an autonomous system,” underscoring the essential role that algorithms, software, and computational processes play in this art form. Unlike conventional digital art, which largely depends on the artist’s skill to manipulate visuals directly, generative art relies on algorithms or sets of rules—often incorporating randomness—to produce unique, unpredictable outcomes. This element of randomness is crucial to the novelty and allure of generative art, ensuring that each iteration is distinct and surprising.

In generative art, the artist designs a system, defines the parameters, and allows the system to take over. This method results in artworks that evolve beyond the complete control of the artist, offering unexpected and aesthetically diverse outcomes. Generative art stands at the intersection of technology, logic, and artistic spontaneity, enabling creators to explore new frontiers that may be inaccessible through traditional methods.

Pandey emphasizes that generative art is a unique blend of creative exploration and computational techniques, resulting in a one-of-a-kind artwork each time—even if the underlying rules remain consistent.

Key Elements and Principles of Generative Art

Pandey identifies the core elements and principles that are crucial for creating generative art that is visually captivating and conceptually coherent. These elements are the building blocks that artists use to craft generative systems that bring their creative ideas to life:

Elements of Generative Art:

- Color: Artists use different hues, values (lightness or darkness), and intensities to make their generative pieces vibrant and engaging. Colors can be algorithmically selected or randomized, resulting in dynamic and often unexpected visual compositions.

- Form: Form refers to the representation of three-dimensional elements in a two-dimensional space. Both geometric and organic shapes can be generated, providing visual depth and complexity to the artwork.

- Line: Lines give structure to the artwork by connecting points or creating boundaries. Variations in thickness, length, and style of lines evoke different moods and contribute to the composition’s overall aesthetic.

- Shape: Shapes are enclosed areas defined by lines or contrasting colors. By randomizing the creation and arrangement of shapes, artists introduce creativity and an element of unpredictability, giving the artwork a dynamic feel.

- Space: Manipulating positive and negative space helps create balance and depth within a composition. The use of space can make a composition appear crowded or open, depending on the desired effect.

- Randomness: Introducing randomness is essential for generative art, ensuring uniqueness in each piece, even when following the same set of rules.

- Texture: Texture adds depth and visual richness to generative artwork. Using algorithms to generate textures allows artists to create images that feel tactile and multi-dimensional, even when displayed on a flat screen.

Principles Guiding Generative Art:

- Rhythm: Rhythm is established by repeating and varying elements to create a sense of movement, directing the viewer’s eye throughout the artwork.

- Contrast: Contrasting different colors, shapes, and textures creates visual interest and tension, which make the compositions stand out.

- Movement: Movement guides the viewer’s gaze across the piece. Artists use gradients, lines, and dynamic color changes to create a visual path that encourages exploration of the artwork.

- Proportion: Proportional relationships between various elements ensure harmony and coherence within the artwork. Properly balancing different components is crucial for maintaining visual stability.

- Harmony: Harmony ensures that all elements work cohesively, creating a balanced composition despite the presence of random variations.

These elements and principles are fundamental in adapting traditional artistic practices into a digital format, creating a visual language that blends algorithmic precision with artistic intuition.

Tracing the Historical Roots of Generative Art

To fully appreciate generative art today, Pandey traces its evolution, beginning well before the age of modern computers. The roots of generative art reach back to the early 1960s, when pioneering artists began using emerging technologies to expand the possibilities of traditional art forms.

The Plotter’s Influence:

Before advanced computing was widespread, early generative artists used mechanical devices called plotters to create their works. A plotter translates computer instructions into physical drawings, and in the 1960s, most plotters were limited to black and white. This constraint heavily influenced the aesthetic of early generative works, characterized by intricate and mechanical line drawings.

Pioneering Artists and Their Contributions:

- Frieder Nake: One of the first artists to use plotters for creating color drawings, Nake’s work, such as “Homage,” explored the interplay of horizontal and vertical lines, introducing randomness to vary the size, scale, and proportions of the elements.

- George Nees: Known for his 1968 piece “Schotter,” which showcases increasing randomness, Nees used the gradual disarray of squares to explore the relationship between order and chaos in visual art.

- Vera Molnar: A significant figure in early generative art, Molnar focused on geometric abstraction. Her work relied on subtle variations, demonstrating how computation could generate intricate visual compositions and paving the way for future artists to explore digital creativity.

- John Maeda: A pivotal figure in bringing generative art into the mainstream, Maeda’s contributions, including “Flora” and the development of Processing, made generative art more accessible. His work helped broaden the appeal of generative techniques, inspiring a new generation of artists and designers.

Pandey also highlights the contributions of women like Vera Molnar, whose pioneering work was instrumental in shaping the early development of generative art.

The Emergence of Processing: A Turning Point in Generative Art

The creation of Processing, a programming language developed by Ben Fry and Casey Reas, marked a significant turning point in making generative art accessible. Processing was designed as a beginner-friendly platform that allowed artists to create code-based visuals without an advanced understanding of computer science.

Democratizing Artistic Creation:

Processing made it easy for artists to experiment with code, providing pre-built functions for drawing shapes, manipulating colors, and incorporating randomness. This allowed artists without extensive programming experience to bring their creative ideas to life in a digital format.

Expanding Artistic Possibilities:

Processing’s capabilities went beyond simple sketches. Artists could use it to create both static and dynamic works, such as animations and interactive pieces. Pandey notes that Processing laid the foundation for many contemporary generative artists, providing them with a versatile toolkit to explore new styles and techniques.

Understanding the Canvas: A 2D Cartesian Plane

In generative art, the digital canvas acts like a 2D Cartesian plane, merging creativity with programming.

Points as Vectors:

In a Cartesian plane, each point is defined by its x and y coordinates, which represent its location. Artists use these vectors to precisely position elements, and through transformations such as rotation, scaling, and translation, they can manipulate these elements to create dynamic visuals.

Creating Lines and Shapes:

Pandey explains how basic programming functions in Processing can be used to create points, lines, and shapes. Adjusting parameters like stroke weight (line thickness) and color allows artists to experiment with different aesthetics, resulting in a wide array of visual effects.

Drawing Curves with Bezier Curves:

To add complexity, Pandey introduces Bezier curves—mathematical tools that enable artists to create smooth, flowing curves that add an organic quality to the artwork. These curves are useful for creating intricate, decorative patterns and provide generative artists with a broader set of creative possibilities.

Understanding these mathematical concepts allows artists to work with precision while also encouraging exploration and creativity.

Harnessing Randomness: A Key Ingredient in Generative Art

One of the core aspects of generative art is the incorporation of randomness to create unique, unpredictable outcomes. Pandey emphasizes that randomness ensures that each generative piece is distinctive, even if based on the same code.

Random Number Generation:

In most programming environments, random number generators are used to introduce variability. Artists use these functions to alter characteristics such as size, position, color, or rotation, ensuring that each output is visually unique.

Visualizing Randomness:

Pandey shows how plotting random numbers results in unpredictable patterns, which is what makes generative art visually intriguing. The randomness ensures that no two executions of the code produce identical results, adding depth and an element of surprise to the artwork.

Introducing Perlin Noise: A More Organic Approach

While pure randomness adds variety, it can sometimes be too chaotic or disjointed. Pandey introduces Perlin noise as a more organic alternative. Developed by Ken Perlin, Perlin noise creates smooth, gradual variations, mimicking the natural randomness found in the real world.

Smooth, Interpolated Randomness:

Perlin noise generates smooth, flowing changes in values, making it particularly effective for representing natural textures such as clouds, water, or landscapes that require softer transitions.

Creating Textures with Perlin Noise:

Pandey provides examples of using Perlin noise to generate visually appealing textures such as marble and clouds. By adjusting parameters like octaves (which determine the levels of detail) and falloff (which affects how smoothly the noise blends), artists can create more natural and visually rich generative works.

Exploring Advanced Algorithms: Genetic Algorithms and GANs

Pandey also delves into some of the more advanced algorithms that have emerged in generative art, focusing on how these technologies are expanding the boundaries of creativity:

Genetic Algorithms:

Inspired by natural selection, genetic algorithms create art by mimicking evolutionary processes. Pandey describes how these algorithms evolve a population of potential solutions, iteratively selecting and combining them based on fitness criteria. This process can be used to evolve visual compositions towards a desired aesthetic, providing a unique approach to generative creation.

Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs):

Generative Adversarial Networks, or GANs, are another advanced tool that has transformed generative art. GANs consist of two neural networks—a generator that creates images and a discriminator that attempts to distinguish generated images from real ones. This adversarial relationship improves the quality of the generated outputs over time. Pandey notes that artists have used GANs to produce highly innovative and surreal pieces that push the boundaries of digital art.

Concluding Thoughts: The Future of Generative Art

In conclusion, Pandey emphasizes the immense potential of generative art as a form of creative expression:

A Unique Form of Creative Expression:

Generative art is a powerful way for artists to explore their ideas through the language of code. By leveraging computation, artists can access realms of visual creativity that would be impossible or incredibly time-consuming through traditional means. Generative art merges the roles of artist and programmer, giving rise to a new kind of creator.

Bridging Art and Technology:

Generative art also serves as a bridge between technology and artistic expression, translating complex computational concepts into visually accessible and engaging forms. This integration fosters a deeper understanding of how technology can be harnessed creatively.

Pushing the Boundaries of Creativity:

Pandey envisions that generative art will continue to push the boundaries of what is creatively possible. As algorithms evolve and computational power increases, the potential to create complex, detailed, and meaningful art will grow, ensuring that generative art remains an essential component of the future artistic landscape.

Pandey’s presentation provides a comprehensive overview of generative art—from its history and technical foundations to its creative possibilities. His insights inspire artists and programmers alike to explore this exciting intersection of art and technology, embracing the power of computation to generate unique and captivating visual experiences.

Leave a comment