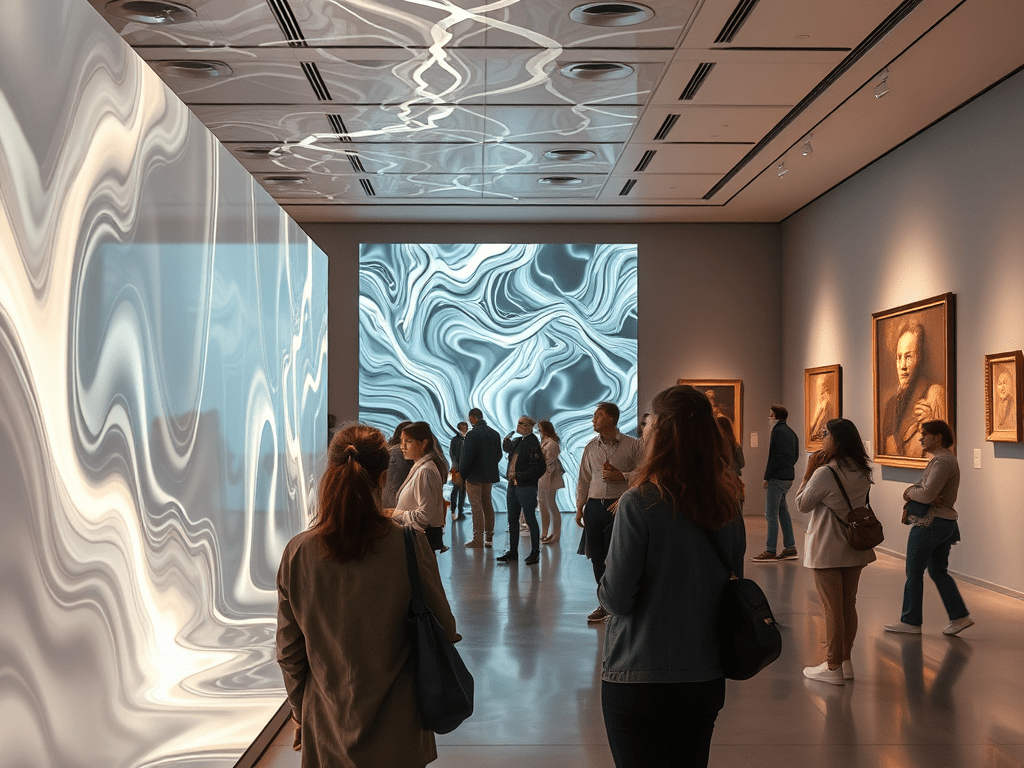

Imagine a large exhibition space in the near future. Visitors enter a gallery illuminated by shifting patterns projected onto massive screens. Each display changes in real-time, guided by algorithms and data streams. These works adapt and transform without any single, fixed form. The room hums with the quiet presence of computational logic at work. The viewers do not stand before static objects but encounter artworks emerging from systems built on code. They experience artifacts created through generative processes, where instructions, constraints, and parameters produce unpredictable results.

In adjacent rooms, the exhibition’s curator has placed carefully selected historical artworks to provide context. The older pieces are from movements like Dadaism, Surrealism, Conceptual Art, and Minimalism. Each represents a time when artists sought to challenge existing norms and explore new approaches to creation. The curator believes that by comparing generative art with these historical precedents, visitors will understand that generative art does not exist in isolation. Instead, it continues a lineage of questioning authorship, embracing chance, and focusing on systems rather than final objects.

This scenario is a thought experiment. It envisions a space where modern generative installations converse silently with older artworks. The aim is to show that generative art’s reliance on algorithms and systems connects it to previous eras when artists also sought to redefine creativity and the nature of art-making. While today’s generative artists use code, data, and automated processes, their inquiries align with artists who, a century ago, used collages, instructions, dream imagery, or geometric forms to explore similar questions.

Generative art stands on the shoulders of these historical movements. Though it employs advanced technology, it shares with them a desire to expand the boundaries of what art can be. It engages with chance as Dadaists once did, delves into the unexpected like Surrealists, values the underlying concept over the final object like Conceptual artists, and applies systematic methods akin to the Minimalists. The following sections consider these precedents in turn, drawing lines of continuity that show how generative art echoes the past while forging new territory.

Dadaism: Embracing Chance and Rejecting Convention

In a section of the gallery, images and texts from Dadaism confront the visitor. These works emerged in the early twentieth century during a period of profound upheaval. World War I had disrupted established values and beliefs. Dadaists responded by rejecting traditional artistic standards. They found meaning in nonsense, chance, and the random. They tore up newspapers and rearranged snippets into poems, pasted unrelated photographs together, and used found materials. Their method allowed unpredictability into the process, undermining the notion of art as a carefully planned statement by a singular genius. Instead, Dadaists saw the accidental as an integral component of their practice.

Generative art resonates with this approach. Although it uses algorithms rather than scissors and newspapers, it similarly welcomes the unforeseen. Consider a generative artwork that relies on random number generators to determine colors, shapes, or movements. The artist provides a framework—a set of instructions—but the actual output shifts according to chance elements in the code or the input data. Just as a Dadaist collage might depend on whatever scraps of paper happened to be at hand, the generative system might rely on variables that cannot be fully predicted.

This connection is not superficial. Both movements ask: is art something that must be controlled at every step, or can it emerge from processes that escape total authorial domination? Dadaists answered by embracing chaos to question conventional taste and meaning. Generative artists, working in a different era, do so by building systems that produce variations the artist did not explicitly design. Both challenge the idea that the artist alone determines the final result. They encourage a perspective in which art is not a fixed object but a phenomenon that arises from processes beyond the artist’s direct influence.

In the imagined exhibition, a visitor looks at a generative projection that evolves in response to random variables. Next to it, they see a Dada collage. Though separated by a century and radically different in medium, both share a spirit of letting go. The visitor notices that, while Dada might have been a critique of societal norms at a time of chaos, generative art does not necessarily present itself as political. Yet it too relinquishes control, letting the unpredictable into the creative act. In both cases, this acceptance of chance leads viewers to question how much of what they see is intentional. The dialogue between these movements reveals that today’s algorithmic randomness is a distant echo of the Dadaist embrace of the accidental.

Surrealism: Accessing the Unconscious and the Unpredictable

Moving to the next room, the visitor encounters Surrealist works. Surrealism, emerging after Dada, sought to tap into the subconscious, the realm of dreams, and the irrational. Artists engaged in automatic drawing, writing, and painting, trying to bypass conscious control and logical reasoning. By doing so, Surrealists aimed to reveal hidden truths and new forms of imagery that could not be accessed through deliberate planning.

Generative art’s unpredictable outputs can be seen as modern parallels to Surrealist practices. Instead of relying on human subconscious impulses, generative systems harness computational logic that can produce results seemingly disconnected from rational planning. The code may contain instructions, but the complexity of the algorithm or the training of a model might yield outcomes that surprise even the artist. This sense of unexpected emergence can evoke a feeling similar to encountering a surreal dream image. The difference is that, while Surrealists tried to remove rational interference through psychological techniques, generative artists leverage non-human processes. The machine, in a way, becomes a source of “unconscious” creativity.

Imagine a generative model that produces strange, dreamlike landscapes based on sets of parameters the artist defined. The output might be eerie or unsettling, filled with forms that defy logic. Surrealists would have recognized in this approach a familiar strategy: bypassing conventional representation to unlock something deeper and less explainable. While Surrealists sought this depth by tapping into their minds, generative artists use algorithms to reach beyond the familiar. The code can act like an external unconscious, producing configurations that challenge viewers’ assumptions.

As visitors compare a Surrealist painting—perhaps filled with impossible creatures, twisted perspectives, and ambiguous symbols—to a generative video installation of evolving, otherworldly shapes, they perceive that both push beyond the ordinary. Surrealists did this to confront the viewer with the strangeness hidden beneath the surface of everyday life. Generative art, though rooted in technology, shares the same pursuit of the unexpected. Both invite viewers to consider that reality, whether filtered through human dreams or algorithmic calculations, is not as fixed or stable as it seems. The aesthetic experience becomes a reminder that art can open portals to worlds unknown.

Conceptual Art: Shifting Focus from Object to Idea

Continuing through the gallery, the visitor arrives at the section devoted to Conceptual Art. In the 1960s, artists began to question the importance of the art object itself. Instead, they focused on the ideas, instructions, and frameworks behind the work. Conceptual artists might present a set of written guidelines for creating a sculpture or a wall drawing. The physical outcome mattered less than the concept that generated it. Sol LeWitt’s instructions for drawings on walls are a well-known example: the final appearance depended on others executing his directions, and multiple versions could exist in different places.

Generative art aligns closely with these principles. It often emphasizes the system rather than the final artifact. The artist writes code that outlines rules and parameters. The artwork is then what emerges when the system runs. The viewer might witness infinite variations generated from the same underlying instructions. This shifts attention away from any single image or object and toward the underlying concept or algorithm. The idea of an artwork as a stable, finished piece dissolves. Instead, the artwork is the entire process, the logic that generates forms, and the continuous unfolding of possibilities.

In this sense, generative art stands as a direct conceptual descendant of the dematerialization championed by Conceptual Art. Just as a set of written instructions can serve as the art, the algorithm can be considered the core artistic statement. The code becomes a set of conceptual conditions from which art emerges. The actual visuals or sounds that appear on the screen or speakers are manifestations of that underlying concept. This approach encourages viewers to think beyond appearances. They may ask: what is the artist’s idea? What principles shape this generative system? What does it mean that the artist relinquishes direct control over the final form?

When viewers in the thought experiment’s exhibition compare a set of Conceptual Art instructions pinned to the wall with a generative piece displaying on a screen, they see that in both cases, the physical presence is not the sole essence. The instructions or code can be implemented in countless ways, in various contexts, producing different outcomes. The art lies in the conceptual structure that guides production. This perspective challenges traditional notions of originality, rarity, and material value. Just as Conceptual Art helped redefine art as something that can exist as an idea rather than an object, generative art reinforces that notion and pushes it further into the digital realm.

Minimalism: Systematic Approaches and Essential Forms

The next room presents Minimalist art. Minimalism emerged in the 1960s as a reaction against the excesses of gestural painting and subjective expression. Minimalists aimed to strip art down to its essentials. They created works that relied on simple geometric shapes, repeating patterns, and industrial materials. These artworks often embraced order, clarity, and repetition. Minimalists were interested in what remained when personal expression and decorative elements were removed.

Generative art relates to Minimalism through its systematic methodology. Minimalists meticulously structured their works, using predefined rules to determine how forms would be arranged. A series of repeated cubes, for example, might be placed in a grid to produce a visual pattern without personal flourish. Similarly, generative artists build algorithms with logical steps that determine how elements are composed. Instead of physically placing cubes, they write instructions that arrange pixels, lines, or shapes according to specified functions.

While the Minimalist aimed to highlight form, space, and material, generative artists highlight the underlying system. Yet the resonance is clear: both rely on defined constraints to produce visually coherent outcomes. Minimalists might have created art by working within a set of self-imposed formal limitations. Generative artists rely on computational constraints encoded as rules in a program. Both limit the influence of subjective spontaneity and rely on a framework that guides the creation process.

When visitors compare a Minimalist sculpture—perhaps a set of identical metal cubes arranged in a measured sequence—to a generative artwork producing dynamic geometric patterns on a screen, they recognize that both arise from systematic thinking. Minimalists found meaning in simplicity and repetition. Generative artists find meaning in the complexity that emerges from simple rules executed at scale. Both share an interest in order, structure, and the aesthetics that emerge from defined systems rather than personal expression or narrative content.

This parallel challenges the assumption that generative art is entirely new. Instead, it shows that the roots of working with systems and rules reach back to a time before digital technology. Minimalism and generative art differ in their tools and their outputs, but they align in their principle that art can come from applying constraints and processes, revealing forms that arise from logic rather than personal gestures.

Continuity and Transformation: Generative Art in Context

Having explored each historical movement, the visitor now returns to the central hall where generative artworks are displayed. The conceptual threads become evident. Dadaism’s embrace of chance, Surrealism’s fascination with the unpredictable and the unconscious, Conceptual Art’s focus on idea over object, and Minimalism’s systematic approach—each of these historical modes shares with generative art an inclination to redefine the creation process and challenge conventional assumptions about what art should be.

Generative art might rely on tools and materials that past movements never imagined. It uses software, computational algorithms, and sometimes even machine learning models. Yet the fundamental questions remain similar. How much control must an artist exert? Can randomness or external processes play a role in creating meaningful art? Is the essence of art located in a final object, or in the idea and process behind it? These inquiries link generative art to a lineage of experiments and challenges that artists have posed for more than a century.

In the thought experiment’s gallery, this continuity helps visitors place generative art within a historical tradition rather than seeing it as an isolated phenomenon. By understanding that Dadaists also let go of control, that Surrealists also pursued the unexpected, that Conceptual artists also prized the blueprint over the artifact, and that Minimalists also relied on systematic structures, viewers see that generative art is part of a broader conversation. It takes historical precedents and reconfigures them in the context of contemporary technology.

Yet this lineage is not static. Generative art also transforms these legacies. While Dadaists might have thrown bits of paper into the air, generative artists use algorithmic randomness that can be mathematically defined. While Surrealists tapped into personal psychic processes, generative artists rely on computational processes that often remain opaque even to their creators. While Conceptual artists wrote instructions, generative artists write code that can run autonomously and evolve over time. While Minimalists used physical materials in rigid formations, generative artists can create complex patterns that unfold infinitely without traditional material constraints.

This transformation highlights that generative art is not a mere repetition of past methods. It stands at an intersection where historical inquiries into chance, meaning, and structure meet the capabilities of digital systems. The computational realm expands the scope of what can be done. Generative artists can model complexity, scale variability, and integrate live data sources. These expansions do not break the continuity with the past; rather, they show how technology can push longstanding artistic questions into new territories.

Extending the Thought Experiment

Imagine the exhibition expands beyond a single gallery. Consider a vast, networked platform accessible online, where generative artworks respond to global data feeds. Weather patterns, financial markets, social media sentiments, and user interactions all influence evolving visual and sonic outputs. In this digital environment, the lineage connecting generative art to older movements becomes more important. Without the historical context, one might assume that generative art is a purely technological phenomenon—just an outgrowth of coding skills and digital aesthetics. But placing it in dialogue with earlier movements reveals a deeper continuity of purpose and inquiry.

In a global, data-driven environment, generative artists still grapple with ideas of control, authorship, meaning, and form. The difference is that now these issues play out at scale and in real-time. Historical precedents provide a conceptual grounding. Dadaists remind them that randomness has long been a tool to question norms. Surrealists show that embracing the unexpected can reveal hidden layers of perception. Conceptual Art proves that systems of instruction, whether written on paper or coded in software, can carry artistic intent. Minimalism demonstrates that stripping away extraneous elements can yield clarity and structural insight.

Armed with this historical perspective, viewers of generative art can appreciate that the digital dimension is not just about novelty. It is also about exploring longstanding artistic questions through new means. This insight can guide critical assessments, helping audiences and critics to understand that generative art’s complexity and dynamism are not ends in themselves, but methods for exploring creative questions that have concerned artists for generations.

Resonances and Differences

Although generative art is connected to these older movements, it also differs in significant ways. Dadaists worked with physical materials and lived in a time of intense cultural upheaval. Their embrace of chance was partly a reaction to the chaos of war. Today’s generative artists might be responding to the complexity of digital networks, artificial intelligence, and the flood of information. The context has shifted. Yet the underlying attitude—welcoming unpredictability as a source of insight—remains.

Surrealists engaged with the psyche and the unconscious mind. Generative artists, instead, engage with computational processes that can produce unexpected outputs without any human psyche involved. The analogies hold at a conceptual level, but the means differ. Surrealists looked inward; generative artists look outward to code and data. Still, both see value in transcending everyday logic.

Conceptual artists challenged the art market and the fetishization of objects by elevating instructions over physical art. Generative artists, similarly, produce code that can generate infinite variations, undermining notions of unique originals. But generative works often exist as digital outputs that can be copied endlessly, raising questions about value and ownership in a digital economy. The root ideas overlap, but the implications differ in a world where digital reproduction is effortless.

Minimalists sought purity in form and repetition. Generative artists also rely on systematic approaches, but they can incorporate feedback loops, interactivity, and complexity beyond anything Minimalists imagined. Minimalism’s clarity contrasts with the potential complexity of generative systems. Still, the shared emphasis on structure and system reveals a conceptual lineage.

These comparisons highlight that generative art both continues and transforms the legacy of past movements. It does not replicate their methods, but it engages with similar questions in a new medium. As a result, understanding generative art as part of a historical continuum allows for a richer appreciation. Instead of seeing it as a detached curiosity or a product of pure technical experimentation, viewers can understand it as another chapter in a larger story of artists questioning what art can be.

Toward an Integrated Understanding of Generative Art

The thought experiment has led the visitor through various rooms, each containing clues to the historical roots of generative art. By the time they leave the exhibition, they have a broader perspective. They see that generative art, though defined by code and algorithms, is not an isolated movement. It participates in an ongoing dialogue about intention, control, meaning, materiality, and creativity.

This integrated understanding can influence how audiences engage with generative works. Instead of focusing solely on the novelty of automated creation, viewers might consider what is at stake in giving algorithms the power to shape aesthetic outcomes. They might ponder why an artist would choose a generative method and what conceptual frameworks underlie those choices. They can also see parallels with older forms of art that grappled with similar questions in different historical contexts.

In educational settings, placing generative art within this lineage can help students and scholars appreciate it beyond the technology. They can analyze it as part of a tradition in which artists challenge conventions, expand definitions, and use unconventional methods to broaden the range of artistic possibilities. This approach demystifies generative art, making it more accessible by showing that its conceptual concerns are not new, even if its tools are.

Conclusion: Generative Art as a Continuing Dialogue with the Past

Generative art’s reliance on systems, algorithms, and a willingness to embrace chance may seem like a radical departure from earlier practices. But as this thought experiment demonstrates, generative art does not stand apart from the trajectory of art history. It builds upon foundations laid by artists who also questioned the limits of control, the significance of randomness, the primacy of ideas over objects, and the value of systematic approaches.

Dadaism, Surrealism, Conceptual Art, and Minimalism each contributed methods and ideas that resonate with generative practices today. Dada’s randomness, Surrealism’s unexpected imagery, Conceptual Art’s prioritization of ideas and instructions, and Minimalism’s structural clarity all echo through contemporary generative works. Although generative art uses different tools—digital code, data inputs, and computational processes—the conceptual lineage is clear.

By recognizing these echoes of the past, we gain a deeper understanding of generative art’s place in the broader narrative of artistic innovation. We realize that while the medium and techniques have changed, the fundamental inquiries remain. Generative art continues a long-standing dialogue about what art can become when artists step beyond traditional boundaries. It confirms that art’s evolution is not a series of abrupt breaks, but a continuous exploration of how to make meaning through form, process, and concept.

In the end, generative art and its artistic predecessors share a common goal: to expand the possibilities of creation. By acknowledging these historical connections, we see that generative art is a chapter in a story that began long before computers and will continue evolving as artists find new ways to embrace uncertainty, redefine authorship, and harness the potential of systems both old and new.

Leave a comment